At Moreschi a plaque in memory of Giorgio Latis

-

IIS Nicola Moreschi - Viale S. Michele del Carso, 25, 20144 Milan

-

27 apr 2023

-

10:00

MILAN IS MEMORY. AT MORESCHI A PLAQUE IN MEMORY OF GIORGIO LATIS

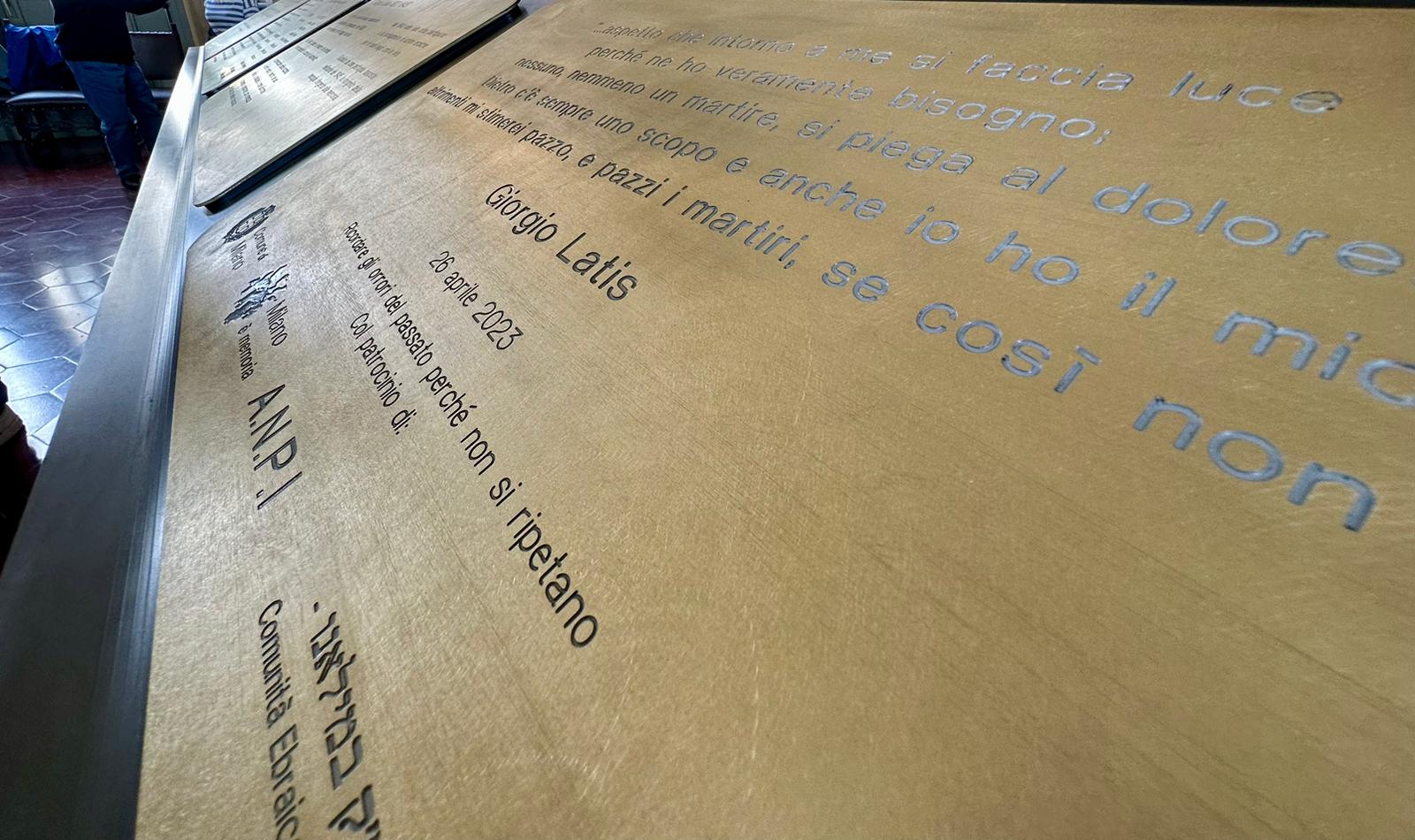

Milan, 27 April 2023 - Today, at 10 am, at theNicola Moreschi Institute of Higher Education (via San Michele del Carso 25), a plaque was unveiled in memory of Giorgio Latis, Jew and partisan, died in Turin on 26 April 1945, expelled from school in 1938 together with other classmates and some teachers following the application of the racial laws.

Below is the story on the persecution of the Jews at Moreschi and on Giorgio Latis for which we thank Prof. Pietro Pittini

The persecution of the Jews by Moreschi and Giorgio Latis.

At the beginning of September 38, with the expulsion from schools - from nursery to university - of all Jews (students, teachers, employees), with a procedure even quicker and more drastic than that adopted in Nazi Germany, the what has been defined as the "persecution of rights" carried out by the fascist regime against them; made increasingly harsh and pervasive in the following five years, it became "persecution of lives" in '43, with the birth of the RSI

The persecution also hit hard at "Moreschi": two teachers, Principal Loria and ten students out of the 431 attending were expelled.

The two teachers, Professor Elsa Della Pergola who taught at the Lower Course (corresponding to the current Middle School) and Prof. Eugenio Levi, who had been serving at the Upper Course for about twenty years now, were put on leave on 16 September, suspended on October 16th and discharged – i.e. fired – on December 14th.

Della Pergola still suffered the consequences of the expulsion after the war, when she had started teaching again, because with each transfer from one institution to another she had to produce documents to prove that the interruption of service was not her fault.

Eugenio Levi already had to his credit - as can be seen from his personal file - around twenty publications: translations and annotated editions of Latin and Greek classics, translations from German, French and English, a Latin dictionary, an Arabic manual. ..After the war he received an award for an essay on theater criticism. This makes us understand how the racist rules that affected Jewish scholars, often forced to emigrate, deprived Italian schools and universities of precious talents for the country.

The professor. Levi, Professor Della Pergola and Principal Loria participated in the rapid establishment of the Jewish school in Via Eupili, given that Jewish students were allowed to continue their studies in separate schools (paid by the Jewish Community), so that they did not pollute with their presence the companions of the presumed "Aryan race"...Levi played an important role both in via Eupili (where he managed to have the September exams taken in '43, with the Germans already occupying Milan) and in the school Jewish in the post-war period, of which it was an important reference until late in life.

The story of Principal Arturo Loria was very different: graduated in Mathematics from the Normale di Pisa, author of texts for his subject, former Principal of other institutes and appointed Director (as it was then called) of the Royal Commercial Institute in 1923, as winner of competition, had the great merit of having obtained the Institute's current headquarters, coveted by many. It hadn't been easy, as is clear from the extensive documentation; it was equally tiring to obtain, with continuous requests and discussions with the Municipality and the Ministry, the indispensable resources for the laboratories and teaching equipment...

And after all these efforts, crowned with success, he was - like his teachers - suspended and then fired, and also encountered difficulties in obtaining his pension. It was a trauma from which Loria never recovered; worn out by stress, he died in December 1939 at the age of sixty-two.

For the expelled students, we did not find a list drawn up at the time, as in other schools, nor are there any individual communications, because enrollment was simply prevented for those who could not declare, with a specific form, belonging to the presumed Aryan race . By cross-referencing various data, it was however possible to ascertain that ten students were certainly expelled; the names, shown on the panel but which we still want to remember, are:

Reinheimer Gerardo, Cicurel Alberto, Eichenberger Renzo, Cohen Mario, Cohen Maurizio and Leoni Ernesto del Corso Inferiore;

Samaia Aldo, Levi Franco, Samaia Silvana and Latis Giorgio del Corso Superiore.

Of the ten, it seems that only one fell into the storm of the Holocaust and the war, and that is Giorgio Latis; Today we rightly dedicate a special space to his memory, because he sacrificed his young life (twenty-five years old!) for our freedom.

He was born in Modena in 1920, but the family moved to Milan in 32 and came to live a stone's throw from the "Moreschi", in Via Verga 15.

An intelligent, lively and restless student (always with an 8 in conduct), a great reader, with vast cultural interests, he was a friend of young people destined to become protagonists of the world of culture, such as Giorgio Strehler, Vittorio Sereni, Franca Valeri. After his expulsion from Moreschi he studied as a private practitioner, graduating in June 1939. By evading the laws against Jews, he managed to work for an electrical installation company. This did not stop him from dedicating himself to what he was most passionate about: together with his cousins Vito, Gustavo and Marta Latis he set up a puppet theatre, adapting texts by Dickens, Lorca, Cocteau and organizing shows in Milanese salons.

In November '43, when the Germans and republicans were now hunting the Jews, he accompanied his parents and sister across the Swiss border and returned to Milan convinced that they were safe. The Latis, however, were rejected by the Swiss; captured by the Germans, they were locked up in S. Vittore and deported to Auschwitz in January 44 with Convoy no. 6, the same as Liliana Segre. The parents were killed upon arrival, the sister survived a few months.

Giorgio did not think about saving himself but joined the Resistance (battle name "il Biondino", later changed to "Albertino") joining the Youth Front, directed by Eugenio Curiel; active in Milan and Brianza, he was arrested for a denunciation and locked up in S. Vittore. However, he managed to escape thanks to his quick wit and ability to improvise during a corvée of clearing the rubble at the Innocenti factory after a bombing (seeing that surveillance was relaxed, he shouted "There's a bomb! Run away!". There was a general flight and he took the opportunity to move away).

He then joined the Action Party and moved to Piedmont, which he traveled tirelessly by bicycle. Here he revealed extraordinary audacity and great organizational skills, taking care of the "Justice and Freedom" formations and arranging sabotages, transports of weapons, recovery of Allied launches. He collaborated with personalities such as Galante Garrone, Ada Gobetti (who remembers him in her “Partisan Diary”), Edgardo Sogno.

He was entrusted with the so-called "Kappa Office", which dealt with assistance to political prisoners. Here he was able to make use of his propensity for the theatre: he was able to enter and exit the "Nuove", the prisons of Turin, assuming false identities; he involved doctors and nurses, carried out prisoner exchanges. He managed to get a partisan to escape from the Vercelli prison and, disguising himself as a Republican officer, took two fellow fighters from the Alessandria prison who were to be shot the next day!

On 26 April 1945 Turin rose up; Latis offered to carry the order to the Resistance formations in the hills to enter the city. He left by car with documents in which he was listed as a doctor. On his way out, he passed the Reaglie checkpoint without problems; on the return, however, there was a different formation of the republican army, more cautious. Giorgio was searched, found in possession of compromising documents and immediately shot on the spot with a burst of machine gun fire.

After a long bureaucratic procedure, slowed down by a date error, in 1996 he was awarded the silver medal of memory.